Drinking and Public Disorder

A report of research conducted for The Portman Group by MCM Research

Historical background

The effects of alcohol on behaviour have been the subject of discussion and scholarly speculation for centuries. In Bickerdyke (1886) we are entertained to an account of the beer shops of Egypt in 2000 BC and the customs associated with, perhaps, the earliest known consumption of ale. Some of Bickerdyke’s comments on the regulation of drinking behaviour strike us as being very pertinent today as he was a fierce antagonist of licensing laws. While recognising that alcohol could sometimes be associated with disorderly behaviour, he was of the opinion that restricting the times and places of its consumption was only likely to lead to more problems:

"To check the evils of drunkenness, we [must] rely not on prohibitory legislation which has been tried elsewhere and found wanting, but on the gradual spread of education and enlightenment."

Over a century later, after the introduction of much prohibitory legislation, we might do well to consider this issue again. We deal with this issue in some detail in Section 7.

Some earlier historical sources reflect a much more negative attitude toward alcohol – one which would not be out of place in some of the more lurid tabloid accounts of contemporary disorder. The scientist Robert Burton, for example, vents his rage at excessive drinking in The Anatomy of Melancholy (1621):

The first pot quenches thirst, the second makes them merry, the third for pleasure, quarta ad infaniam, the fourth makes them mad. If this position be true, what a catalogue of madmen shall we have? What shall they be that drinks four times four? … they are more than mad. Worse than mad.

Similar views are expressed by Heywood in Philocothoinista or the Drunkard Opened, Dissected and Anatomised (1635). Heywood attempts to convert the reader to sobriety and temperance and recounts his life’s attempts to do the same. Thus, a farmer rebukes him – How shall I pay my landlord ? Were it not for drunkards, I should sow no more barley! His own anti-drink rhetoric is, perhaps, less subtle:

"The horrid vice of drunkenness and intemperance, which like the cup of Cyrces, turns men into beasts … rude, ignorant, ill-nurtured, shameless, ill-tutored and unmannerly; who neither observe their betters, nor reverence their elders, regarding not matrons, nor respecting virgins: who not only are of that impudence, to utter sqirrulous and obscene speeches in their hearing, but in their absence to asperse their charities; boasting what either they have, or might have done … caper, toy, laugh, sing and prattle, troubling the whole company with their antic gesticulations and tedious verbosity … Let every bashful and modest man avoid drunkenness, for it is a monster with many heads, one of obscene talk, others of blasphemy, prophamation, lying, cursing, wrath, murder … Nay, have not some husbands slain their wives when they have come home from swilling? And wives cut their husbands throats after they have been tippling? The father has flung his knife at the mother and missing her, killed the child; one brother has slain the other in the tavern and one man stabbed his dear friend in the alehouse."

Missing from such diatribes, of course, is any real examination of the extent to which the effects of alcohol are mediated by other factors such as the circumstances in which drinking takes place, mood, personality factors etc – all those variables which today are generally held to be essential in any ‘scientific’ discussion. Rather, Burton and Heywood are content to hold up drinking as the root of most social ills – simple philosophy taken up by the Methodists and the Temperance movements some 200 years later. Ironically, of course, the Temperance movement came some 50 years after what most historians feel was the era of maximal abuse of alcohol - the high level of gin consumption and its associated ‘palaces’. (Brander,M. 1973)

For a more considered approach to the problems we have to wait until the late 1930s and the seminal work of Tom Harrisson and the Mass Observation Unit. Here we find social scientists actually prepared to venture out to the pubs and surrounding streets of Bolton to discover for themselves what actually happens. Here we find a view which is neither pro- nor anti-alcohol but which rests on a calm and objective account of real-life behaviour. Commenting on prevailing attitudes, and the lack of objective data, at the time, Harrisson observes:

"The trouble is that sociologists and temperance men are seldom pub-goers. To them the pub opens on to a mystery. Who goes in and what happens there they don’t know. But from this doorway there reels a succession of figures that can be recorded under the headings of drunks per 10,000 of the population, and later as victims of cirrhosis. We have seen how few of the people who come out of these doors are had up for being drunk or do die of cirrhosis."

Harrisson also refers frequently to the macho image associated with drinking which was evident among his informants and, as we shall see later, has been so prominent among our own. He quotes an anonymous reply to a local newspaper survey organised by the Mass Observation Unit:

"My reason for drinking beer is to appear tough. I heartily detest the stuff but what would my pals think if I refused? They would call me a cissy."

Another of the Bolton informants emphasises the role of drinking in providing a little excitement in an otherwise dull and depressing life:

"What can a chap do in a one-eyed hole like this? He’d go off his chump if there were no ale, pictures and tarts."

Harrisson’s comments on the effectiveness of restrictions placed on drinking echo those of Bickerdyke and, again pre-empting Section 7 of this report, are ones with which our own research has led us to concur:

"It is an absolutely basic assumption in contemporary licensing practice that the length of time a pub is open directly affects drunkenness. It is no better supported by demonstrable facts than the other assumption [that drunkenness is related to the number of pubs]; the experience of almost every country on the Continent disproves it. We have suggested that this inhibition on the pub’s times, the rigorous enforcement of time limits on drinking, has had an effect in making the pub seem in a special way ‘immoral’."

The appeal of forbidden fruit was also noted by Doris Langley Moore, whose lucid arguments against the ‘nanny-state’ approach to licensing appeared in the News Chronicle in June 1939:

"Licensing regulations, like many other old-fashioned methods of dealing with potential evil, were framed under the simple illusion that you can prevent people from doing something they want to do by placing difficulties in their way. The most acute students of human behaviour have long been aware that, on the contrary, difficulty frequently acts as a first-rate incentive, and forbidden fruit tastes far sweeter than that which drops into the hand … I believe that, if we were given the freedom permitted in this respect to almost all other peoples of Europe, there might at first be some slight excess, but in a very short time we should adjust ourselves to the idea of being treated as rational creatures, and would behave as such."

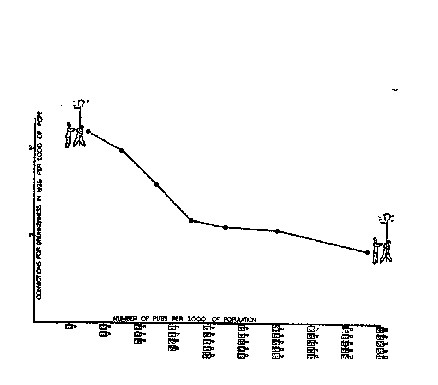

The idea that the number of pubs in a locality is somehow related to levels of drunkenness is given an interesting twist by Harrisson. He provides data, drawn from the Government licensing statistics, to show an inverse relationship between the two, as shown in Figure 2.1.

The Pub and The People is both reassuring and depressing. On the one hand, it chimes perfectly with our own research material. It shows that ‘lager louts’ are not a novel product of the late 80s. As the sanguine policeman in Tuck’s report commented, "T’was ever thus". The patterns of behaviour which led to a ‘Moral Panic’ on a scale which was previously aimed at other ‘Folk Demons’ such as football hooligans and skinheads seem to us so uncannily similar to those which Harrisson and his researchers described. Consider this account of the ‘lads’ on a night out in Blackpool in 1938:

"Along the promenade the air is full of beersmell, that overcomes seasmell. It arises from people breathing. A swirling, moving mass of mostly drunk people, singing, playing mouthorgans, groups dancing about. Chaps fall over and their friends pick them up cheerfully and unconcernedly. At one spot a young man falls flat on his face, his friend picks him up and puts him over his shoulder, and lurches away with him. Immediately a fight starts among four young men: the crowd simply opens up to give them elbow room as it flows by; some stop to look on. One of the fighters is knocked out cold and the others carry him to the back of a stall and dump him there."

The routine events we have witnessed, whether in Wakefield, Banbury or any of our other research sites seem little different. This is, perhaps, the depressing side. The traditions of British drinking, with all their boorish qualities, are still alive and well. Although, as we will be at pains to argue later, the sensationalised stories of death and destruction on the streets at closing time paint a far from accurate picture of nights out in our major towns and cities, few of us would want to spend too much time there.

The other depressing feature of The Pub and the People is that it is so good and still, almost 50 years on, has a sense of immediacy and accuracy for anyone who spends much time in working class boozers. It makes our own research seem (pun intended) small beer in comparison. I hope, however, that we have maintained some of the crucial characteristics of the Mass Observation Unit’s approach – spending time in the right places, talking to the right people and taking seriously the things which they have to say.

Figure 2.1